Default Risk

Every bond carries some risk that the issuer will fail to fully repay the loan (or “default”). Default risk (also known as credit risk or counterparty risk) is the risk that a borrower will not make payments as promised. Credit risk is closely tied to the potential return of an investment. Most notably, the interest rate on bonds is strongly correlated with its perceived credit risk. The greater amount of perceived credit risk, the higher the interest rate the borrower will be required to pay.

In most instances, independent credit rating agencies are called in to assess the default risk of a bond issuer or specific bonds. These credit ratings not only help investors evaluate risk, but also help determine the appropriate interest rates on individual bonds. For more information on bond ratings and bond insurance, see Bond Ratings & Bond Insurance.

For more information on bond ratings and bond insurance, see “Measuring Bond Risk” above.

Interest Rate Risk

Bond prices have an inverse relationship to interest rates. If an investor chooses to sell a bond before it matures, the price he can receive will be based on the interest rate environment at the time of the sale. If market interest rates have risen since the investor “locked in” his return, the price of the security will fall.

Reinvestment Risk

Reinvestment risk (otherwise known as call risk) is the cash flow risk resulting from the possibility that callable bonds will be redeemed prior to maturity. The practice of calling bonds is also known as “prepayment” or “refunding.” In most cases, an issuer will call bonds and simultaneously reissued new bonds to take advantage of a lower interest rate environment. Bondholders receive payment on the face value of the bonds, plus any penalties for early redemption. This forces the investor to reinvest the principal sooner than expected, usually in a less favorable environment (one with lower interest rates).

Inflation Risk

Inflation risk is simply the risk that inflation will undermine the performance of an investment. For example, an investor expects the inflation rate to average 3.5% for the next 10 years. As a result, he purchases 10-year bonds with an average return of 4.5%. If inflation unexpectedly jumps to 5.0%, the investor will actually experience negative “real” (inflation-adjusted) returns on his investment.

Liquidity Risk

Liquidity risk describes the danger that a given security or asset cannot be sold quickly enough in the market to prevent a loss (or make the required profit).

Assets, such as the stock of a publicly traded company, are generally highly liquid and have low liquidity risk. Other assets, such as houses, are highly illiquid, yet have high liquidity risk. Since the bond market is considerably thinner than the stock market, the simple truth is that when a bond is sold on the secondary market, there may not be a buyer.

It should be noted that liquidity risk is virtually nonexistent for U.S. Treasury debt. Treasury securities are generally considered the most liquid securities in the world.

Country Risk

Country risk is the risk associated with holding assets in, or undertaking transactions with, a particular country. Sources of risk may be political, economic, or regulatory instability affecting profits, currency stability, taxation, nationalization, etc. Country risk varies from one country to the next. Some countries have high enough risk to discourage foreign investment.

Bond Ratings

Independent credit rating agencies are called on to evaluate the credit worthiness of financial obligations issued by governments or businesses and to issue a credit rating based on their findings. A credit rating is a rating agency’s opinion on the general creditworthiness of a debt issuer or the creditworthiness of an issuer with respect to a particular debt security or other financial obligation.

Long-term ratings generally include financial obligations with original maturities greater than one year. Bonds rated in the BBB-/Baa3 category or higher are considered investment-grade; bonds rated lower than BBB-/Baa3 are considered high yield, or speculative.

During the credit rating process, the rating agency analyzes the issuer’s financial condition and management, economic and debt characteristics, and the specific revenue sources securing the bond. Upon completion of its analysis, the rating agency assigns a credit rating based on the issuer’s likelihood of default. A lower rating is indicative of a bond that has a greater risk of default than a bond with a higher rating.

In general, credit rating agencies use a letter assigned rating system. The letter indicates the level of risk for a given investment, which affects the interest rate investors are willing to accept in return. For example, a highly-rated security (e.g., a AAA rated municipal bond backed by a stable government agency) has a low interest rate because it is a low-risk investment. Conversely, a lower-rated security generally carries a higher interest rate in order to attract buyers to this high-risk investment. In this case, a higher interest rate is being provided in exchange for the investor taking on the risk associated with a higher likelihood of default.

Investment-Grade vs. Speculative-Grade

Investment-Grade Bonds

Investment-grade bonds are perceived to be of higher credit quality and lower risk of default compared to lower rated, speculative-grade bonds. A bond is considered investment grade if its credit rating is BBB- or higher by Fitch Ratings or Standard & Poor’s, or Baa3 or higher by Moody’s.

Speculative-Grade Bonds

Speculative-grade (also known as “non-investment grade,”“high-yield,” or “junk”) bonds are typically issued by issuers with troubling fundamentals and questionable ability to meet their debt obligations. While a speculative-grade credit rating indicates a higher probability of default, this higher risk is often offset by higher yields. In some instances, bonds may receive an investment-grade credit rating, but are later downgraded to speculative-grade if the issuer’s fundamentals deteriorate, and vise versa.

Rating Inconsistencies

Based on historical default rates, municipalities have exhibited significantly lower default rates than corporate borrowers of the same credit rating. For example, an “A” rated corporate bond would carry more risk than an “A” rated municipal bonds. In acknowledgement that municipalities were being held to a different standard from corporate and sovereign debt, Fitch and Moody’s began a recalibration of their municipal ratings in 2010, attempting to bring municipal ratings in alignment with other sectors

Bond Insurance

The credit quality of a bond can be enhanced by bond insurance, which is provided by an insurance firm that guarantees the timely payment of principal and interest on bonds in exchange for a fee. Insured bonds receive the same rating as a corporate rating of the insurer, which is based on the insurer’s capital and claims-paying resources.

For example, a bond repaid after one year is viewed as less risky than the same bond repaid over 30 years. After all, over a 30-year period, any number of factors can negatively impact an issuer’s ability to pay bondholders. The additional risk assumed by a longer maturity has a direct impact on the interest rate an investor is willing to accept in return. In other words, an issuer will pay a higher interest rate on longer-term bonds. An investor, therefore, has the potential for greater returns on longer-term bonds, but does so in exchange for a greater level of risk.

Treasury Yield Curve

Image for illustration purposes only.

Normal Yield Curve

Image for illustration purposes only.

Flat Yield Curve

Image for illustration purposes only.

Inverted Yield Curve

Image for illustration purposes only.

Bond issuers and investors need to know how bond market prices are directly linked to economic cycles and concerns about inflation and deflation. As a general rule, the bond market and the overall economy benefit from steady, sustainable growth rates. Moderate economic growth benefits the financial strength of governments, municipalities and corporate issuers which, in turn, strengthens the credit of those bonds.

But steep rises in economic growth can lead to higher interest rates, as investors anticipate higher future inflation. Increasing interest rates will erode a bond’s value and will demand a lower price in the marketplace. Fear of this pattern is what causes the bond market to fall after the government releases positive economic news, such as positive job growth or a greater number of housing starts than was anticipated. Since rising interest rates push bond prices down, the bond market tends to react negatively to reports of strong and potentially inflationary levels of economic growth. The opposite is also true: negative economic news may indicate lower inflation and, therefore, may positively impact bond prices.

A bond’s duration is the weighted average, in years, of the present value of a bond’s cash flows. Duration will be affected by the size of the regular coupon payments and the bond’s face value. Bonds with higher durations are more volatile and carry more risk than bonds with lower durations.

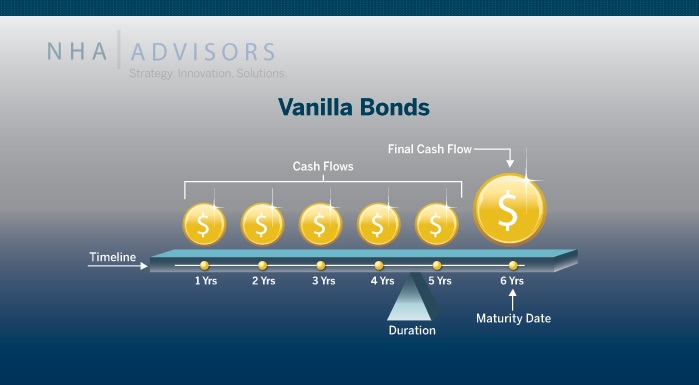

For each of the two basic types of bonds, vanilla bonds and zero-coupon bonds, the duration is described in further detail below:

Vanilla Bonds

Since vanilla bonds include a series of scheduled payments prior to the bond maturity date, duration will always be less than its time to maturity.

Consider a bond that has annual coupon payments and matures in six years. In this scenario, cash flows consist of six coupon payments, with the last payment including the final coupon payment and the face value of the bond.

Image for illustration purposes only.

The dollar signs in the teeter-totter diagram above represent the cash flows an investor receives over the six-year period. To balance the teeter-totter at the point where cash flows are equal on both sides of the pivot point (or duration), the pivot point must be at some point before maturity. Unlike a zero-coupon bond, a vanilla bond makes coupon payments throughout its life, and therefore, repays the full amount of the bond sooner (it has a shorter duration).

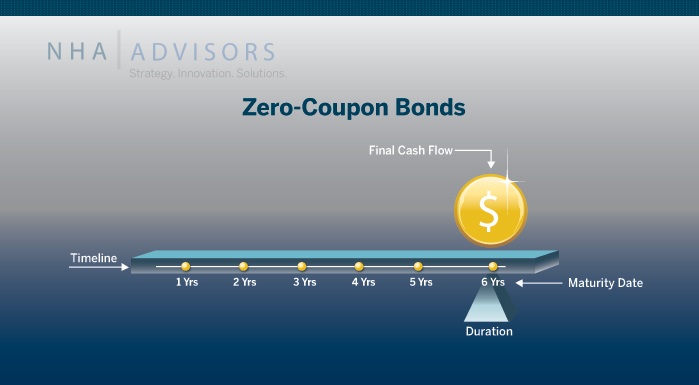

Zero-Coupon Bonds

Unlike vanilla bonds, zero-coupon bonds do not make periodic coupon payments. Zero-coupon bonds have only one large payment (the face value of the bonds) on the bond maturity date. Since there are no regular coupon payments and all cash flows occur at maturity, the time to maturity and duration are equal.

Image for illustration purposes only.